The Joy and Power of Art Education:

the origins of the International Baccalaureate

Visual Arts programme (1)

Visual Arts programme (1)

(A little side-step from my story of A Life Painting Music)

Around May 1980, as the local IB art examiner, I walked in to the final IB art exhibition of an eighteen year old student, all ready to make a critical appraisal. Within seconds, I could see that something remarkable had taken place. She asked me to sit down and insisted that I drink a small plastic cup of milk, while she explained her main art work. It was called The Milky Way: a composition comprised of plaster casts of small dolls' heads and of her own breasts, all intertwined as something like an umbilical cord. As I tried to drink what was presumably cow's milk, I realised with some emotion, that this exhibition and our interview was going to be intensely personal. The rest of her work was a series of sensitive abstract pastels of womb-like and embryonic shapes. "So what happened to you?" I asked. She told me how, against her teacher's advice, she felt compelled to give visual form to a traumatic loss and to share this with the viewers of her show. I leave you to guess the rest. I gave her a high grade for having the courage to find such an intimately personal form for her art work. She had far surpassed the requirement that IB art work had to reflect personal research and experience. I'm sure that her presentation of that exhibition was enormously therapeutic. The power of art.

This example is seriously thought-provoking, but IB students also produce works of technical excellence in joyous colour, form and joie de vivre. The ones that stick in the mind are those where the student has used his/her art as a process of exciting self-discovery. You would like to meet them today, to see how are doing.

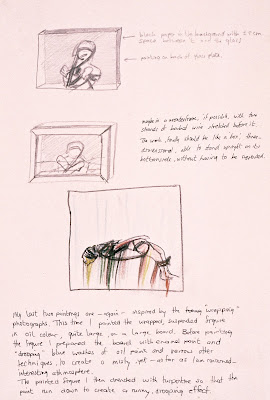

My deep conviction was (and is) that every high school student should enjoy some form of artistic appreciation and endeavour, as an essential part of their education. This is not about becoming an artist - it's about how the self-confidence that comes from the exhilaration of artistic achievement can and does overflow into other disciplines. The experience will change their life. The aims and criteria of the current IB Visual Arts exam, somewhat modified since my day, can be found here. "The visual arts are an integral part of everyday life, permeating all levels of human creativity, expression, communication and understanding" (from the IB syllabus). Below are a few untitled examples.

In 1975 I was asked to join the wonderful team of IB pioneers at work in Geneva. In those early days there was no real Arts Syllabus, only a hotchpotch of national exams with wildly different standards. What a challenge! My task was to create a high-quality art education syllabus with a world perspective and a respect for all cultures, a syllabus with standards that would be accepted by universities and art colleges internationally. Today, over one million students in four thousand schools worldwide enjoy the opportunities of IB schools.

My first step was to organise an international conference of art teachers, including exemplary enlightened teachers like the Austrian-American Herb Holzinger in Vienna, the British Glyn Uzzel in Geneva, the Dutch Marten Post in South Wales and the Danish Flemming Jørgensen on Vancouver Island. I believe that you can only truly educate from personal creative experience; significantly, all of these teachers were prolific artists - their own creative activities and those of other unnamed teachers would enlighten and inspire thousands of students. Naturally, they were all to become my good friends.

After the Second World War, there was a lot of discussion about ways in which the arts could contribute to inter-cultural understanding and world peace, but as time went by, art education theories had almost become an incestuous perpetuum mobile. Too much talk! So my question to our conference was: "What do we understand by art education from a world perspective? And how are our convictions supported by our own creative experience in visual arts?"

One talented student confronted me with an apparently chaotic display of photographs, scattered over the floor and walls. They all had pieces torn out of them or were mutilated and I was asked to walk on some of them. I tried not to be prejudiced, to ignore the conventional expectation of a well-arranged exhibition and to figure out how to start. So I asked her "what's your theme?" She said "The fragmentation of memory". Right away, she had me on my toes with her highly intelligent thesis on this phenomenon, including reference to family issues and the influence of time on our aesthetic preferences. After a stimulating discussion, I asked her what she was going to study. It was philosophy, at Oxford. Wow!

Some work was crazy and chaotic, yet revealed intelligent creative uses of materials. A girl asked me to walk into her show blindfold. Hey, wait a minute - this is about visual art! She wanted me to feel the materials and textures of her hanging works before I viewed them.

The traditional narrow Western perspective on what "qualifies" as art needed to be fundamentally replaced with a cross-cultural perspective on the world through a wide-angle lens. We originally called the programme "Art and Design", to encourage multi-dimensional experiments of all sorts. The result was often startlingly adventurous work worthy of the studios of any art college.

Part Two next time. My thanks to all the students whose work illustrated this blog.

______________________________________________